This page documents the evolution of printing and publishing during the fifteenth century. The main event from this era is Gutenberg’s invention of a printing press that works with movable type. It revolutionizes the production of books and pamphlets. By the end of the century printing presses can be found in more than 250 cities around Europe. Such presses can produce 3,600 pages per workday, compared to forty by typographic hand-printing and just a few pages by hand-copying. The books printed between the 1450s and the end of the fifteenth century are called ‘incunabula’. One of the main challenges of the industry is distributing all these works. This leads to the establishment of numerous book fairs. The most important one is the Frankfurt Book Fair which is first held by local booksellers soon after Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press.

1423 – First woodcut printing on paper

Even though woodcut is already used for printing on cloth for over a century, the first European woodcut printing on paper happens in the early 15th century. It is used for printing religious images and playing cards. Woodcut is a relief printing technique in which text and images are carved into the surface of a block of wood. The printing parts remain level with the surface while the non-printing parts are removed, typically with a knife or chisel. The woodblock is then inked and the substrate pressed against the woodblock. The ink is made of lampblack (soot from oil lamps) mixed with varnish or boiled linseed oil. This printing technique is also called block printing. One of the earliest examples of European woodcuts is the image of Saint Christopher shown below. It was printed in 1423 and then manually colored in.

The first complete block books or xylographica are produced in Germany and Holland around 1430. They continue to be produced until around 1480.

1424

Books are still rare since they need to be laboriously handwritten by scribes. The University of Cambridge has one of the largest libraries in Europe – constituting just 122 books.

The parchment that books are written on is so expensive that books that are no longer relevant are not thrown away. The old text is scraped off and replaced by a new one. These reused books are called palimpsests. Using UV light historians can often still read the original text, making these books an important source for ancient texts.

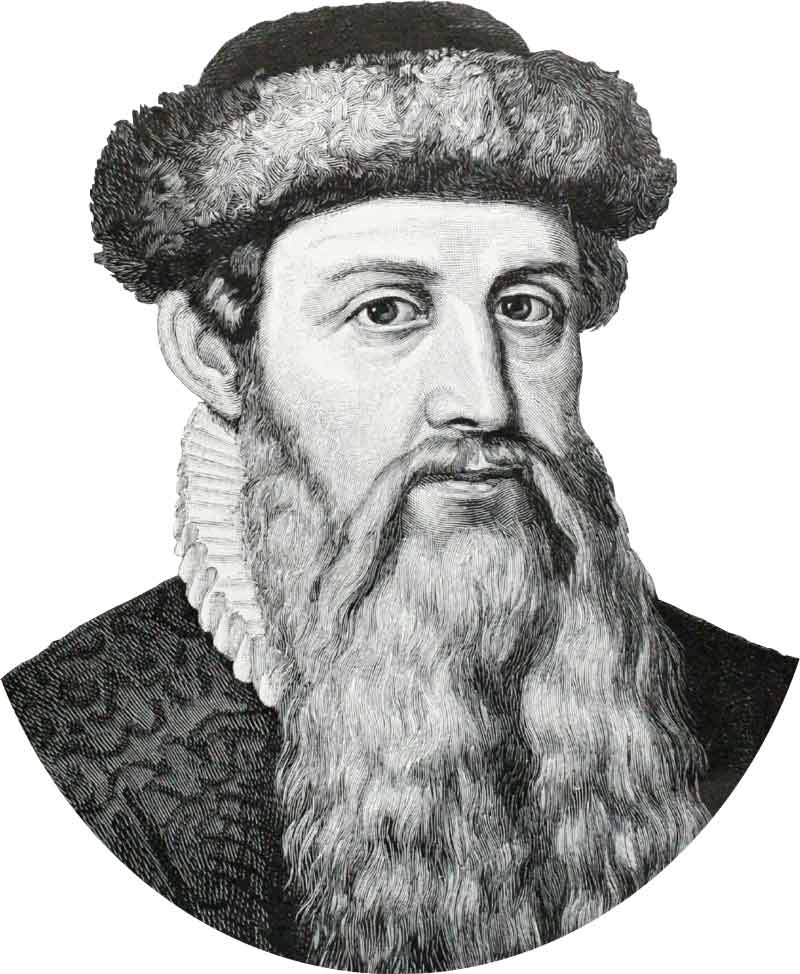

1436 – Gutenberg starts working on a printing press

It takes Johannes Gutenberg, the German goldsmith, inventor, printer, and publisher, four years to finish his wooden press which uses movable metal type. The image below shows a replica of a press from that era. It uses relief printing: at the bottom left a frame holds the columns of text that get printed. This type consists of individual letters set in lead. After inking the type, a sheet of paper is put on top. Next, the frame is shoved to the right underneath the platen. By moving the large handle pressure is applied to make sure the ink is transferred to the paper. Afterward, the bed is moved back to its original position and the paper can be removed.

The press itself is based on the wine presses that were already in use for centuries in that region. Relief printing, through woodblock printing, also isn’t new. Movable type had already been used in the East. What Gutenberg does is bring these various technologies, including the proper type of oil-based ink, together. His real innovation is the molding system that enables a printer to create as many lead characters as are needed for printing a book or pamphlet.

Stephen Fry hosted a Timeline episode about the history of the first printing press. The one hour video can be viewed on YouTube.

1448 – Gutenberg sets up a printing shop in Mainz

Among his first publications printed using movable type are the ‘Poem of the Last Judgment’ and the ‘Calendar for 1448’. Around 1450 Gutenberg begins printing bibles, initially using 40 lines of text in each of the two columns but later switching to 42 lines to reduce page count.

1453

Constantinople is captured by the Turks. Many books from its Imperial Library are burned or carried away and sold. This marks the end of the last of the great libraries of the ancient world.

1455 – Gutenberg Bible

Gutenberg finishes printing between 160 and 185 copies of his 42-line bible which is referred to as the Gutenberg Bible. It is considered the first mass-produced book. The text is set using a gothic type that mimics handwriting. Customers can have their copy decorated manually. A quarter of the books are printed on vellum, the others use paper.

Ironically enough Gutenberg goes bankrupt in 1455 when his investor Johann Faust forecloses on the mortgage used to finance the building of the press. Faust gets hold of the printing equipment as well as the copies of the bible that have already been printed. While trying to sell them in Paris Faust tries to keep the printing process a secret and pretends the bibles are hand copied. It is noticed that the volumes resemble each other and Faust is charged with witchcraft. He has to confess his scheme to avoid prosecution.

1457 – First color printing

The first known color printing is used in ‘Mainz Psalter’, a book containing a collection of psalms. It is printed by Johann Faust and his son-in-law Peter Schöffer. Color, in this case, does not mean full-color images but simply the use of additionals color to highlight some initials, words, or paragraphs. In the Psalter black, red and blue ink is used. It is also one of the first books to contain a colophon, a page, or part of a page that describes who printed the book, the location of the printer, and its production date.

1460 – Catholicon

The first printed edition of The Summa grammaticalis quae vocatur Catholicon, or Catholicon, appears. This Latin dictionary dates back to the 13th century. The printed edition uses a typeface that is a third smaller than that of Gutenberg’s 42-line Bible, lowering its production cost significantly. It is most likely the last book printed by Gutenberg himself, who dies in 1468.

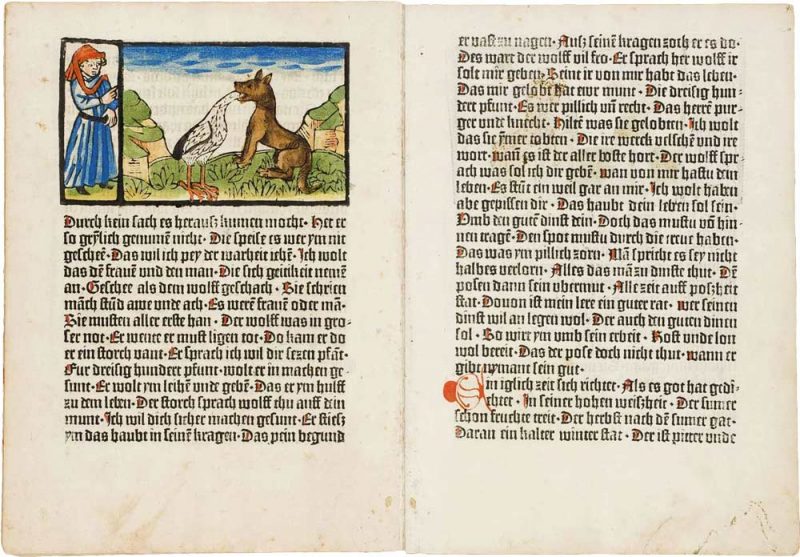

1461 – First books with woodcut illustrations

Albrecht Pfister prints the first illustrated books using a number of woodcuts that are colored in manually. The example below is from a book of fables called Der Edelstein. Another of his books, the Biblia Pauperum, also contains many hand-colored illustrations. Pfister is also one of the first to print books in the German language.

It is estimated that a third of the books printed before 1500 are illustrated.

1464 – Printing arrives in Italy

German monks operate the first printing press in Italy in the Abbey of Santa Scolastica at Subiaco. In 1467 Ulrich Haan (Udalricus Gallus) is the first one to print books in Rome. Haan had emigrated after his letterpress print shop in Vienna was destroyed because he had dared to print a lampoon against the mayor. The first book to be printed in the Italian language is Il Canzoniere by Francesco Petrarca in 1470.

1467 – First engravings

In Bruges, Colard Mansion prints De cas de nobles hommes et femmes (De Casibus Virorum Illustrium), the first book that is illustrated with engravings. An engraving is made by incising a metal plate with a tool called a burin. This plate is then warmed up so that the ink applied to it becomes fluid and also fills all those tiny holes and lines. Next, the ink on the flat surface is swiped off, so that only the nooks and crannies are still filled with it. A slightly moistened paper sheet is placed on the plate and sent through a rolling press. Its pressure makes sure the paper picks up the ink from the drawing. The process is more cumbersome and slower than woodcut printing but engravings are more robust than woodcuts so that more copies can be printed. Drawings can also be more detailed. Over time this technique will replace woodcuts. Colard also prints the first books in English and French.

Another famous engraver from that era is the Master of the Housebook, a south German artist whose ninety-one prints are extremely rare.

1469 – Use of roman type

In their print shop in Venice John and Wendelin of Speier are probably the first printers to use pure roman type, which no longer looks like the handwritten characters that other printers have been trying to imitate until then. Another printer in Venice, Nicolas Jenson, produces a more distinguished roman font which still serves as a model for type designers today.

The fact that most of the books printed between 1450 and 1480 are almost indistinguishable from handwritten manuscripts is down to the conservatism of their buyers. It takes a few decades before legibility is valued higher than convention.

1470 – Title pages & page numbers

Some things we now take for granted were not present in early books. Examples of these are a title page and page numbers. Peter Schoffër, an apprentice of Johannes Gutenberg, is the inventor of the title page while Arnold Therhoernen, a printer in Cologne, is one of the first to use both a title page and page numbers.

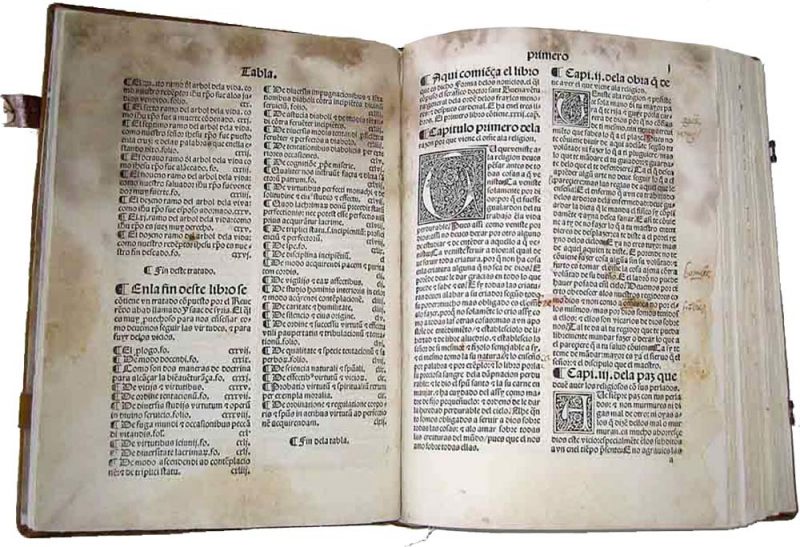

1472 – Book printing takes off in Spain

Sinodal de Aguilafuente is the first book printed in Spain and in the Spanish language. Its printing was ordered by the bishop of Segovia, which is why printing did not take off first in any of the major Spanish cities, like Barcelona or Madrid.

1475

‘De honesta voluptate’ (On honourable pleasure) is one of the first printed cookbooks. It is as much a series of moral essays as a cookbook. Ten years later ‘Kuchenmeysterey’ (Kitchen Mastery) becomes the first printed German cookbook.

1476 – William Caxton introduces metal type in England

William Caxton buys equipment from the Netherlands and establishes the first printing press in England at Westminster. Books printed by Caxton include Chaucer’s ‘The Canterbury Tales’, ‘Fables of Aesop’ and many other popular works. Caxton is also the first English retailer of printed books. The painting below depicts Caxton showing his printing press to King Edward IV.

1481

There are around 40 printing shops in both Germany and Italy. In the Netherlands, printing takes place in 21 cities and towns. Some of the printing houses are large. in Nuremberg, the German printer Anton Koberger employs 100 people for punch-cutting, typesetting, operating 24 presses, and bookbinding. He owns two paper mills, has agents selling his works all over Western Europe and yet finds the time to father 25 children.

1482 – First print shop in Denmark

Johan Snell introduces printing in Odense. Dutch printer Gotfried van Os (Gotfred of Ghemen) establishes the first print shop in Copenhagen in 1493.

1492 – ‘In Praise of Scribes’

De laude scriptorum manualium is a book by the German Benedictine abbot Johannes Trithemius in which he criticizes the effect that the printing press has on the customs and devotion of the brotherhood of monks. Only by copying the Scriptures can a scribe become in touch with the Word of God. The abbot is a complex man who actually sees that printing also offers advantages. He expands the library of his abbey from around fifty items to more than two thousand, many of them printed. His own treatise also is printed since that is the most cost-effective way to spread the message.

1493 – The Nuremberg Chronicle

Anton Koberger, a publisher and printer in Nuremberg, prints his most famous book, the ‘Nuremberg Chronicle’. It is illustrated with hundreds of woodcuts, many of them portraits. These portraits are all imaginary and the same block is often used to depict different persons.

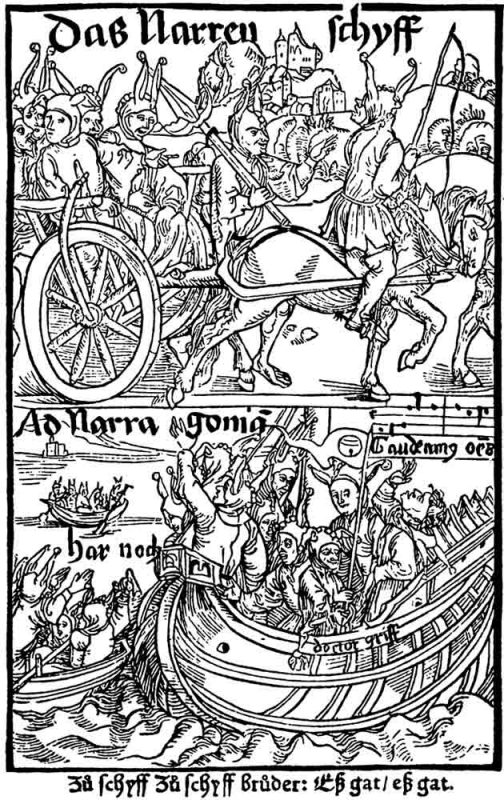

1494 – Das Narrenschiff

Das Narrenschiff (The Ship Of Fools) by Sebastian Brant is published in Basel, Switzerland. This satire about the state of the church is illustrated with woodcuts from the great Renaissance artist-engraver Albrecht Dürer. It quickly becomes extremely popular, with six authorized and seven pirated editions published before 1521.

Dürer’s own ‘Apocalypse’ is another very popular book of that era, published simultaneously in Latin and German. Prints of the detailed woodcuts, such as The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse shown below, are also sold separately.

1495

The first printed books are published in Danish and Swedish. Earlier books used Latin. During the 15th century, around 75% of all printed matter is in Latin, 8% is in Italian and another 8% is in German. England and Spain are the only countries in which the majority of works are printed in the local language.

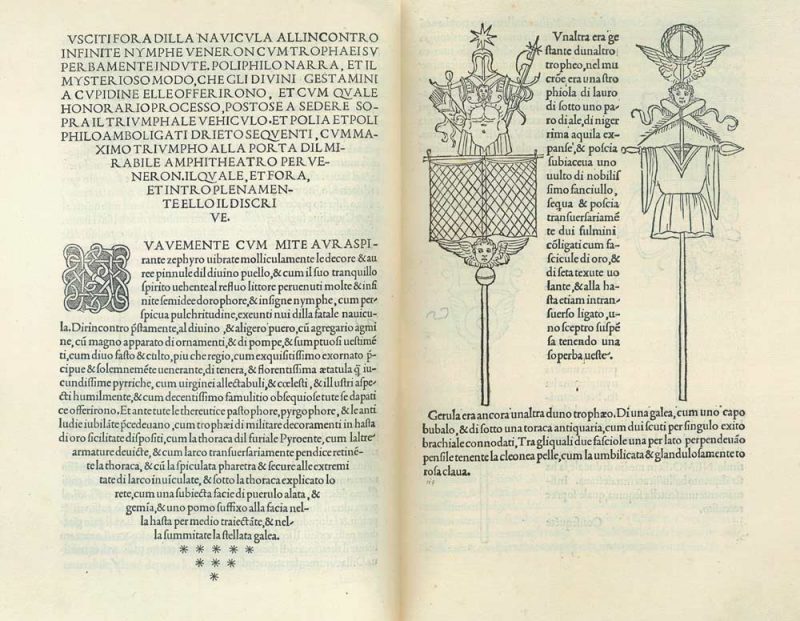

1499 – Aldus Manutius & Francesco Griffo

Aldus Manutius, who had helped found the Aldine Press in Venice in 1494, is the first printer to come up with smaller, more portable books. Until then books are large and heavy, meant to be read while standing at a lectern or reading stand. Manutius’s books are smaller and can be carried around and read anywhere. The book format is called an octavo (‘in eight’) because each press sheet is folded three times to create eight pages. For each edition up to 1000 copies are printed, instead of the customary 100 to 250. To cram as much text as possible on pages, Manutius is the first to use the more compact Italic type, designed by Venetian punchcutter Francesco Griffo. In 1499 the Aldine Press prints Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, an illustrated book set in Bembo. It is considered one of the masterpieces of Renaissance publishing. At the turn of the century, Venice is the center of the book industry in Italy, with around 150 presses in operation.

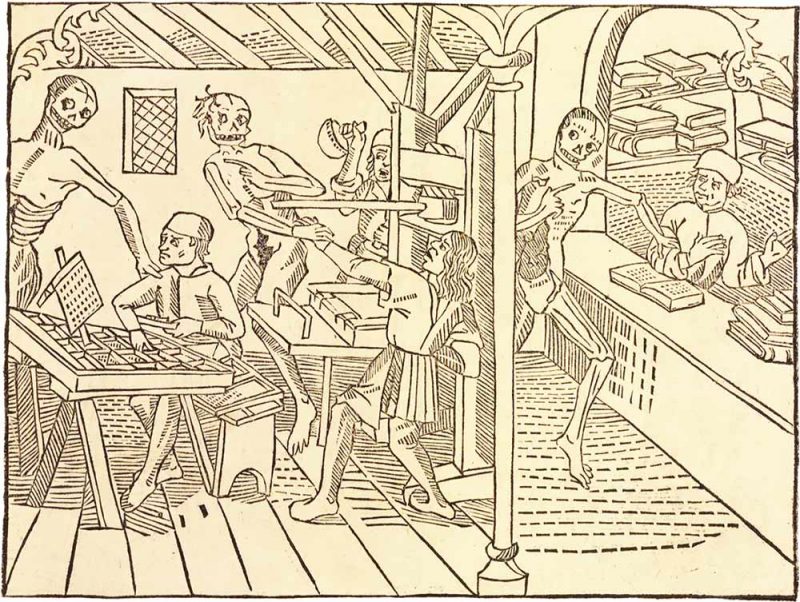

Also from 1499 is a version of Danse Macabre, a picture book about how nobody can escape death, with the first known depiction of a print shop. This book is printed by Mathias Huss in Lyon, France.

Pretty sure China had the first Printing Press or process. This European push is not accurate at all…. Printers Know this, unless they are from Europe.

This page covers printing from 1400 to 1499 and makes no claim that Gutenberg invented printing. Check out the previous page which does mention that printing was invented in China. It also documents printing in Japan and Korea.

How many books in the Gutenberg Bible?

It is a single volume. If you meant to ask how many copies were printed: either 158 or 180, depending on the source. The website of the British Library mentions: It is now thought that Gutenberg produced about 135 copies on paper and about 45 on vellum.

Mostly the rags were carefully selected linen rags – well used. Just processing and preparing these took six to eight months before they were beaten by trip beaters in water to produce a liquid suspension of pulp. This was sieved to make sheets, dried, and then sized with gelatine to create a good writing or printing surface. Altogether a long, and complicated process requiring great skill and labour.

I didn’t know a gelatin coating was added. It reminds me of the Koalin clay that is nowadays used as a filler in paper production.

Informative. Thanks for taking the time. I’m a printer from India, and do a lot of educational printing. Just thinking, where would my livelihood be without Gutenberg’s invention?

They were writing it, not printing it

The Japanese were producing woodblock prints from the 8th century, over 600 years before Europe. The first woodblock print on paper was not European.

tnx for this. i am a 12 year old boy. i needed this for my research.

I have in my possession, a rather unusual print which came out of Nurnberg. I don’t know much about it, but I believe the printing method used was the first of its kind. I have been searching for years to find someone who could tell me more about it. Could anyone here perhaps assist?

Michael Scott translated Aristotle into Latin by 1231 but the ‘de animalia’ did not become an important factor in the progress of science until 1499 when Theodorus of Gaza published a printed version, in Latin, from the copy he rescued from Salonika in 1476. In the 1500’s Aristotle became widely accessible to students.

interesting.

I am an Italian born Australian illustrator for reproduction. And a great fan of Albrecht Durer. His career and broad range having much in common with mine. Thank your for your informative site.

What would we do without the Printing Press?

Best Wishes.

Reading this for the very first time because I was given as an assignment in a Printing Technology Class really makes me more interested in knowing more about Printing. Good Job!

Hi do you know how they made paper out of cotton rags

It seems like it wouldn’t be that interesting, but printing history is really quite fascinating, especially when you think about all ripples that printing caused in society and politics.